The name "100 oxen" of this website ties in with a wonderful joke the poet makes in

Il 6.234-6:

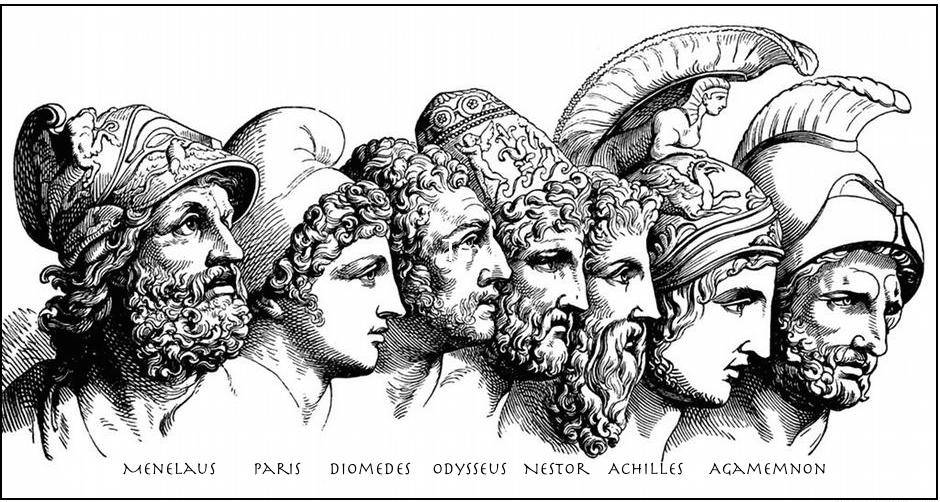

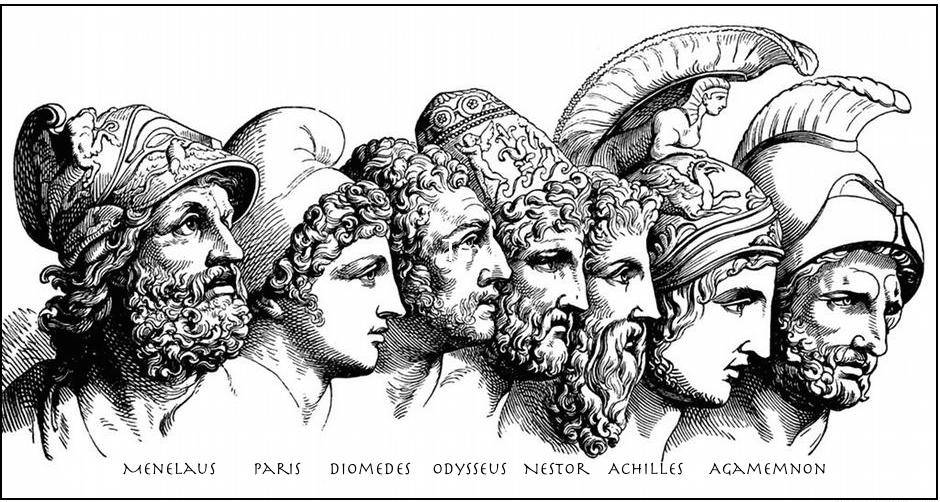

(Diomedes and the famous Trojan ally Glaucus meet on the battlefield. They boast, prepare for a duel,

then discover that their families are old guest-friends. So they decide not to fight but to swap armour in honour

of each other)

This is not only an ironical comment on the likelihood of acquiring your "golden armour", your superhero status (like Achilles), by meeting an old friend in battle and exchanging gifts with him. It is also a summing-up of the whole Iliad: a hecatomb of nine oxen. The nine being the 8 members of Agamemnon's council or the eight little birds caught by the snake in Aulis (Il 2.308-), plus Achilles the motherbird. This is the poet asking us, the eager-for-glory listener: "do you think it will be like that?" just as he asks us this when he lets Achilles pray to Zeus "I will stay here but I will send my comrade out to battle [...] let him come home unharmed" (Il 16.239-) or when he lets Hector's second in command say:"The army is in terrible trouble! You know what, you go down to the city, visit the women and and tell them to pray, while we hold the line here" (Il 6.73-). Are we so gullible that even there we do not see the irony?