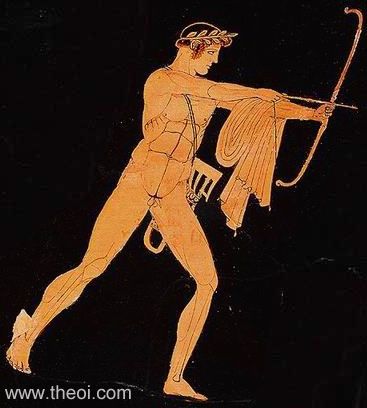

poetry, prophecy and healing - and archery

If Apollo the lyre-player is the god of aoidē (sung epic poetry) and the Iliad is this kind of poetry, it is reasonable to suppose that the god has some special part to play when he appears within this poem. His role at the very beginning of the Iliad seems to confirm this, but first we should discuss some of the likenesses used in this context.

- Arrows: words are like arrows. If they are the right words, they fly straight into the listener's heart and have their (pleasant or painful) effect there. They fly straight because they are like feathered arrows. The words are "ἔπεα πτερόεντα", the usual - not very good - translation is "winged words". The whole Iliad is like a rain of words attacking (the myth of) Menelaos and his war to get Helen back. Pandaros' arrow is "μελαινέων ἕρμ' ὀδυνάων" (Il 4.116-): "fraught with black pain" just as the poem is.

-

Bow: a bow is like a lyre, because it is also stringed. Apollo is the god of both. A clear

explanation of this is in Od. 21.406-, where Odysseus is the only one who can string his bow. When he plucks it, it even "sings" beautifully.

The poet is like an archer -

The Iliad is very much a man-killing poem. Scores of Greek warriors die in the course of the story

and the main heroes (Patrocles, Achilles, Hector) die or will soon die. I am quite convinced that this

is very unusual in traditional heroic poetry. Meanwhile, the Greek public is listening to this and enjoying

it immensely. Since the poem is really about them, this paradox never ceases to amaze the poet who

comes back to it again and again, beginning with Il 1.2-5 where he seems to describe his public as "dogs and

birds" who have come to a feast-meal (dais(1)) to eat their fill. In this

respect, the Iliad can be said to be like a "nousos", a disease sent by Apollo killing many men (who he jokingly insults by

mentioning "mules and swift dogs"). "And a terrible sound came from his silver bow" (Il 1.49).

The "man-killing" Iliad is typically sung during a feast-meal for which many animals have been sacrificed. Both the feast and the poem can be called a hecatomb. The poet's final major scene, the slaughter of the suitors in the Odyssey, is a wonderfully ironic picture of the bard and his typical audience(2). - "Silver bow" is an epithet of Apollo. Achilles has a lyre with a silver crossbar (Il 9.187), a thing which "is-like" a silver bow. I bet Homer also had one like that.

- Apollo has his bow and a quiver on his shoulders. "on the shoulders" is of course a well-known trope in riddles: you carry your head there. This is where you keep your arrows, "ἔκλαγξαν δ' ἄρ' ὀϊστοὶ ἐπ' ὤμων χωομένοιο"(1.46), and the arrows made a fearsome sound from the shoulders of the angry one. For "shoulders" see also Od 23.275 where Odysseus carries a winnowing shovel on his shoulder. This is a thing that "separates the good from the bad".

Apollo the healer

Apollo answers two prayers by Chryses:

1. punish the Achaians (1.43)

2. protect the Achaians (1.457)

which is exactly the program of the Iliad. This is why the Iliad is a paean, a healing song: to give thanks for or to boast of a successful cure. See Achilles' aristeia, Il 22.391. It may cure a person

or a whole community. A military victory is also a cure: a community under siege or otherwise in trouble may be stressed, fearful, feverish. To get rid of this unbearable stress they have several options. They might offer votive gifts

to mythical heroes who in the past did save their people from similar disasters. A wise local leader might order

a bard to sing appropriate epic tales to boost their courage and give them hope. Another possibility is the

sacrifice of a pharmakos, a scapegoat. Also connected to Apollo. Achilles is also like Thersites (he voices the

same criticism) who is, in his capacity as "worst of the Achaians", another candidate for scapegoat. The same

could be said of Achilles before Patrocles' death: his refusal to fight and criticism of the commander-in-chief

could make us call him a shirker or even a coward.

There is the military option: a successful chasing away of the enemy would be the best cure of all. Patrocles

and Achilles do this (for a while), this makes them healers also.

The wrath of Apollo

Why is Apollo angry? Because Agamemnon dishonoured his priest Chryses ("Golden") by abducting his daughter and refusing the priest's pleas to give her back. Is Apollo such a fussy god that he reacts to a relatively small detail in a harsh war that has been going on for many years already? "Why now?" we would like to ask the god who protects Troy. For the poet it is a major topic: he uses it to start off the Iliad - the poem about the war that is waged because a Trojan abducted an Achaian girl, Menelaos' wife. There is no small irony here. The irony is continued when the "abduction" theme is transferred to Achilles(3), the proxy for the listener himself. How can you do this to Achilles when you are going to war because it was done to you? Phoebus, the epithet of Apollo, means "pure" or "bright". It is easy to see how the abducting of girls to satisfy the desires of the army (and the king) is a miasma, a pollution of purity. Note that they have to purify themselves after the girl is shipped back and before offering a sacrifice to Apollo (Il 1.313). Hence the wrath. But in the Iliad, Apollo is not angry because of the abduction of a girl, he is angry because of the dishonour done to his priest Chryses. Why does the poet construct it this way? We must understand that the Iliad always works on the principle of "imagine you were in that situation". It never uses abstractions like "it is wrong to do such and such". So he gives us a figure we can identify with: a father whose daughter has been taken. Or a father who loses his beloved son in a useless war, like Priam and Peleus. Or a father whose child will be killed and whose wife will be enslaved (it is a very patriarchal society). Homer always goes for the pathos and the fact that he mentions those things at all is not a sign of his objectivity, it is his attempt to transfer his own anger to the listening public.

far-shooter

A number of epithets of Apollo describe him a working or shooting from afar. Traditional or not, this fits in with my view of the poet as an exile, one who keeps his distance to his home city. In battle, an archer can be useful but the fact that he also keeps his distance from the swords and spears gives his métier a suggestion of cowardice. Pictures like "helping from afar", "encouraging from behind" etc. occur all through the Iliad. This already starts with Chryses going far away to pray (1.35) and Apollo sitting far away to shoot (1.48).

Apollo the prophet

"ἦ ποτ' Ἀχιλλῆος ποθὴ ἵξεται υἷας Ἀχαιῶν": "soon the sons of the Achaians will be in need of Achilles". To Achilles, this is an oath; he will not come though they need him. But in the subtext, where it is all about the contemporary troubles of the Greeks, it is a prophecy: you are going to need an Achilles to save your city. With respect to Smyrna, he was right: it was under constant threat from its eastern neighbours until it was sacked in the late 7th century. Apollo made the poet a prophet.