from: Alt-Smyrna, I: Wohnschichten und Athenatempel, by Ekrem Akurgal.

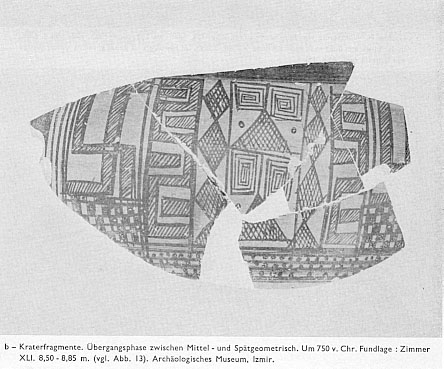

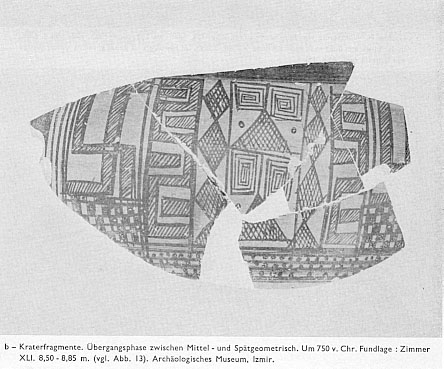

The above picture shows how "ring composition" works in the abstract patterns of vase-decoration. It is also a well

known feature of Homeric (and other) poetry but so far it has been established only at the basic level of the text.

See e.g. below, the ring composition of Odysseus' speech at Il 9.229-306.

In the Thematic Structure presented here, I try to show that rings occur at multiple levels, so that complete low-level rings can themselves be a part of a higher-level ring. So, in my structure, the ring "Odysseus offers the gifts" is itself the central part of a ring called "Embassy to Achilles" (Il 9.1-9.713) which is a part of a still larger ring called "Embassy & Assembly 2: the embassy to Achilles" (book 8, 9 and 10) and so forth.

The rings I identify here are not formal structures. They are themes of the poem, consisting of sub-themes which are ordered in specific ways: in rings, like ABCBA, or as repeated sequences, like ABCABC. A special case of the latter are catalogues, longer sequences of similar themes (AAAA...), e.g. the catalogue of ships and men, the individual games in Patrocles' funeral games, the Epipolesis in book IV.

The process of finding the thematic structure of the Iliad involved first dividing the text into short segments (mostly < 10 hexameters) which represent as much as possible a single topic. These segments are then gathered together into larger "themes" in such a way that they fit together naturally and bring out the organisation of ideas that govern the text.

The relationship between corresponding themes in a ring or sequence is not always clear at first sight. They are always connected by a likeness, e.g.: Agamemnon making an offer - Achilles refusing it; Zeus to sleep - Zeus awake. There may be focus on the same protagonist, the same sort of action, or some god's presence and absence, etc. Within the category of the likeness, there may be a significant contrast, especially in higher-level themes. So: the gods may help you - the gods may deceive you or the immortal hero - the mortal hero.

The analysis of the structure can be important for the following reasons:

This thematic structure is not meant to describe a formal structure, it is a - no doubt imperfect - attempt to recreate a plan of the poem, an inner structure to organise its composition and possibly to serve the singer as a memory-aid during performance. Writers who immediately write down what they compose do not need such an elaborate structure. Rhapsodes who only recite a part of the poem do not need it either. The listening public needs all its concentration to follow the singer - it has no time for structures. I see this as a composer's aid, to keep a handle on the material: created by an aoidos who composed this poem in his head, knew it by heart - he certainly did not improvise - and refined his poem and this structure over many years and many performances.

So, whether or not the Iliad was written down at an early stage, it was not composed with the help of writing or such an elaborate structure would not have been necessary. But there are some anomalies in the structure that make me think that writing did play a role: see here.

A low-level example: Odysseus' speech in book IX, trying to persuade Achilles to help the Achaians:

9.223 comments on the "equal meal" (this really belongs to the previous theme)

9.228 (A) we will perish if you don't fight

9.232 (B) Hector is here, raging

9.247 (C) save the Achaians, you'll regret it if you don't

9.252 (D) Peleus' words: put away quarrels, friendliness is best, it

gives honour...

9.259 (E) put away your anger

9.264 (F) catalogue of gifts / these will be yours...

9.299 (E) ...if you put away your anger

9.300 (D) but if you hate Agamemnon and his gifts...

9.303 (C) pity the Achaians, for they honour you like a god

9.304 (B) now you can get Hector who is raging

9.305 (A) no one else is up to him

Odysseus goes neatly from point to point till he reaches the

central statement, the catalogue of gifts. Then he works back through a

series of shorter points in reverse order to the starting statement:

"only you can do it".

Not all is ring-structure though. Achilles, in his answer to Odysseus,

goes through the same series of points twice:

9.307 (R) Achilles: don't try to sweet-talk me

9.312 (A) I hate liars, I will not obey

9.318 (B) I gave him everything

9.332 (C) he took the girl from me

9.346 (D) Hector will beat you, but I will sail home

9.369 (A) tell the others: he cheated me

9.378 (B) I will not fight for any amount of treasure

9.388 (C) I will not marry his daughter

9.401 (D) I will take Thetis' advice and go home

9.421 (R) Tell the leaders their plan will not work