The story of Helen and the Trojan War was a Charter Myth

for the Ionian migration in the same way the story of

Heracles' children claiming their inheritance was a charter

for the Dorian invasion. These stories functioned as political banners

and were actively promoted by leaders of those movements,

in this case: a channeling of migration from all over Greece to

Ionia, through Athens.

This migration had a dual purpose: to relieve the homeland of population pressure

and increasing competition for land and other resources, but also a military

purpose in the target lands: to build up slowly, in the course of several generations,

a force that could occupy the lands of Western Anatolia - Troy.

It is easy to see why: travel through today's western Turkey and you will see

that the floodplains of the rivers "Gediz" and "Büyük Menderes", then called the Hermus

and the Meander, are prize land, larger and more fertile than any land in

mainland Greece. A nice powerbase for any clan with royal aspirations.

So the "Ionian migration" was not a massive attack, it was a slow infiltration. It was

to be led and directed by one powerful family: the Neleids, who had a power base in

the city of Athens. They had once ruled in Pylos and claimed Poseidon as their ancestor.

In the Iliad they

are represented by Nestor and Poseidon).

This plan probably took its inspiration from the so-called "Dorian Invasion". Of this we know

little, but it is clear that the Dorians did come, and archaeologically there are no

traces of a massive attack and conquest. So, probably the same principle of slow infiltration,

"directed migration", under a political banner: a charter myth. The Neleid plan, however, failed.

The eastward conquest turned out to be impossible, and migration to Ionia had to be stopped

(Od 17.383-) and directed elsewhere. This must have created some tension among the powerbrokers

in Greece.

If this is true, it is easy to see that the

Iliad, singing about a Greek defeat, is a very political poem and that the poet would need a "hidden"

level of meaning to discuss these topics. Ionia in Homers day was a

society under threat of war and Homer was writing about this war.

Although he created an epic distance by, for instance, not mentioning

Ionia and by stressing the fact that these stories took place a long

time ago ("conscious archaization"), he still would have made a lot of

enemies by his stance. He effectively says: "Zeus will give us

Troy one day, but not now".

I place Homer in Smyrna, and Smyrna's Troy was Sardis, the main stronghold of

the not-yet-unified Lydians. These were the people that Smyrna built its

imposing wall against though that did not stop the Lydians sacking their city by the

end of the 7th century.

The Iliad, while set in Homer's past, is about a crisis of his present day: the failure of the Ionian migration. "νῦν ἄμμε παλιμπλαγχθέντας : now that we have been rebuffed" (Il 1.59). The stream of people had to be redirected to the west, to the Black Sea and to "Libya". We may suppose that the Iliad dates from the time before this decision had been taken, and the Odyssey from a later date when the new migration policy had already been effectuated.

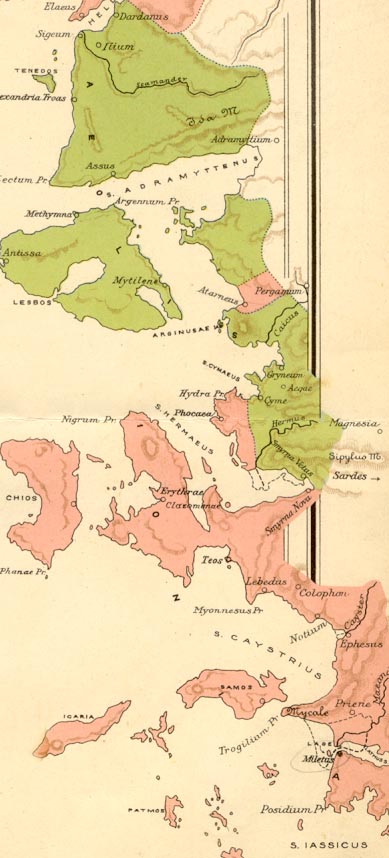

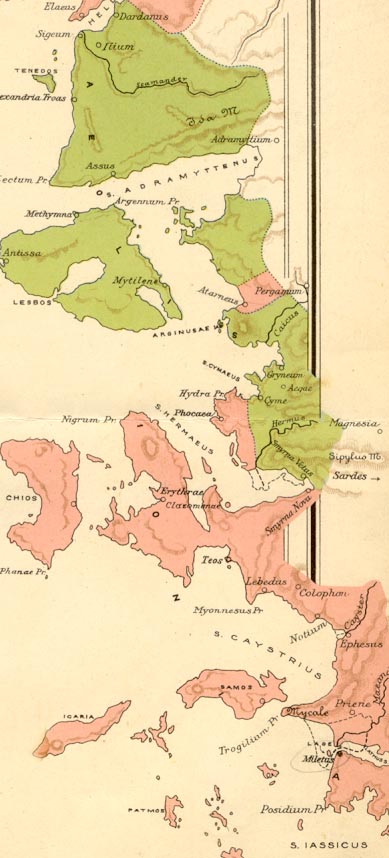

A glance at the map will show how little they succeeded. After a number of generations of this Ionian migration they still found themselves on a small strip of land on the coast, "leaning against the shore" (Il 16.67-), as Homer calls it, unable to defeat the inhabitants of the plains who were both numerous and skilled in fighting. This caused a crisis for, while immigration went on, the available land did not grow. So the Neleids' plan had to be put on hold, emigration redirected to other lands. Miletus, for instance, even became the mother city to a large number of settlements elsewhere.

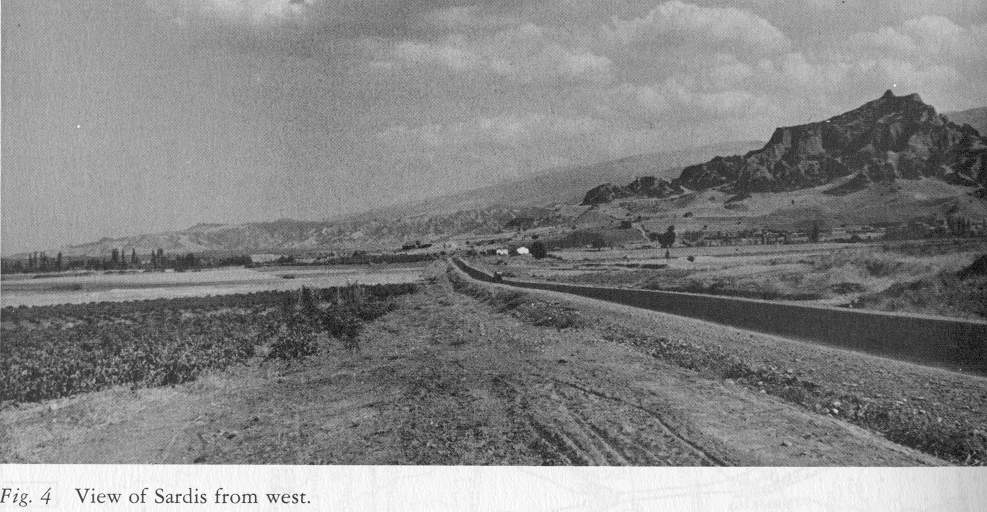

The focus of Homer's story seems to be on Smyrna, situated near the Hermus delta, separated from the plain by mountains. The Hermus plain, later to become Lydia the richest country of the time, was not yet unified but it was led to a degree from a high, impregnable stronghold called Sardis.

As the poet Mimnermus of Colophon (his name means "remember the Hermus") testifies, troops from Colophon and Smyrna fought many a battle in this plain, without success.

Sardis is Smyrna's Troy. The city lies near the confluence of two rivers (like Homer's Troy): the Hermus and a small tributary, the Pactolus, coming down from mount Tmolus. Also like Homer's Troy, there are hot springs nearby (Il 22.149). And, unlike Schliemann's Troy but like Homer's, it has a high citadel on a steep rock (Od 8.508 and Il 15.71 "Ἴλιον αἰπὺ").

The Greeks could not win on the battlefield. There is a simple reason behind this. They were excellent warriors, somewhat later they they became very popular as mercenaries. But the locals were a match for them, if only because there were many more of them. And there were two river plains to conquer so they had to beat two armies. If all the Ionian cities came together as one army of a few thousand men, they could possibly conquer one of the floodplains. But then they would have to leave their cities defended by "old men and children" and open to attack by an army from the other plain. So this never happened.

Homer says (Il 8.557-9): 1000 fires burning with 50 Trojans and allies each. Hanfmann(1) estimates the population size of The Hermus plain in Croesus' time (later than Homer) at 40-80.000. So even if Poseidon could shout like 10.000 men (Il 14.148) it would hardly be enough to conquer one of the river plains. If you would gather all the Ionian men from all their cities, you would have a pretty large army. But then, conquering one plain, they would have to leave their cities undefended and vulnerable to an attack from the other plain. Which would happen, because their eponumous gods, Lydos and Kar, are brothers (Hdt. 1,171).

Homer hints at another policy, the only thing the Greeks could do: wage a low-level war. Enlarging your territory village by village. See for instance the scene on Achilles' shield "the city at war", Il 18.509-. Also, the repeated mention of the λόχος, the ambush, as the measure of a man's courage (cf. the name Ἀντίλοχος, "good enough for an ambush"). What they probably did was slowly enlarging their territory by terrorizing neighbouring farms and villages, killing the men and abducting the women if they could. If a revenge attack came by a large army, they could withdraw behind Smyrna's strong wall. See Il 5.784- where Hera shouts like 50 men (the typical number for an ambush) and Ares shouts in reply like 10000 men (Il 5.860). There is another hint in the Odyssey, where Odysseus tells (a lying tale) about his "Egyptian" exploits, where they raided coastal villages but the population had inland relatives, more numerous and better armed (Od 17.426-). Also the Ismarus episode (Od 9.39-).

So it must have become clear that the Ionian plan was not working. Emigration was felt to be necessary but the destination would be elsewhere. This must have caused tension within the Greek aristocracy, after all, all the Neleids' work turned out to be for nothing. Ionia had to "choose the sea" as its domain. This they actually did and it turned out well for them. East was not a way they could go, as proved by the presence of the Lydians, Cimmerians and later the Persians. So emigration was rerouted to the west and to the Black Sea.