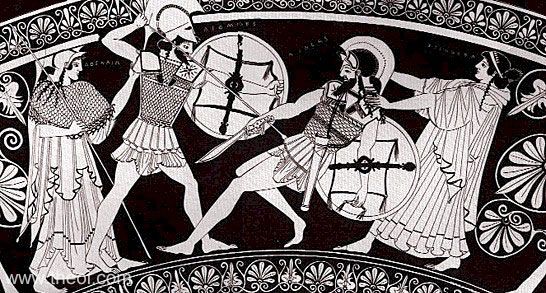

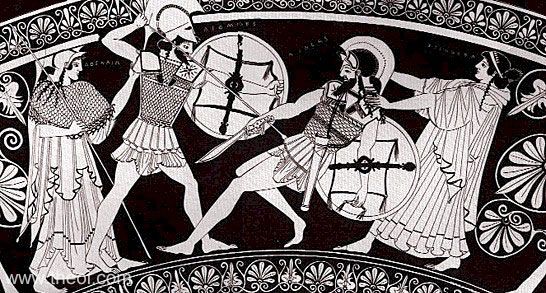

Picture from theoi.com

Here we have the lion's head of the beast. Diomedes' aristeia seems to be a discussion of the role of the gods on the battlefield, in relation to individuals as well as to the whole army. The gods Ares, Aphrodite, Apollo, Hera and Athena come to the foreground while Zeus remains only a spectator. Apparently the "plan of Zeus" of Il 2.1- has not kicked in yet. Diomedes is a young hero who is learning what battle is like and how to survive and win fame. The image is ironical, not because his learning is untrue or invalid, but because it asks the young listener a question: "do you really think it will be like that?"

Like Achilles, Diomedes is dissed by Agamemnon, undeservedly, in front of his troops. Yet he does not quarrel nor develop a mēnis, instead he acts like the perfect soldier and defers to the commander of the army (Il 4.370-). He does not forget it though (Il 9.29-). An important theme is introduced here: a comparison with his father Tudeus.

He is unstoppable like a river in flood, until a bowman (Pandaros, Il 5.95-) hits him in the shoulder. This does not stop him though (as it does in Agamemnon's aristeia, Il 11.368-), he does what one is supposed to do in the Homeric world: pray to the gods, Athena in this case. She teaches him how to be a great hero, and survive. This is effectively the same thing she teaches Achilles even though it is phrased in slightly different terms. It is in the subsequent behaviour of the two heroes that we see the connection. First of all, you have to be really brave. Lead from the front, keep going when others are willing to stop, be prepared to fight anyone. But, secondly, you have to be able to distinguish gods from men. Gods are the ones who decide our fate and you want to avoid directly opposing them in battle. Diomedes obeys this, as demonstrated by the "three times... and the fourth..." scenes which he has in common with Patrocles and Achilles.

"Recognizing the gods" in Homeric terms comes down to knowing what is the motivating force behind your own acts. It is related to Proteus' ability to tell you "which of the gods is angry at you" (Od 4.423) and, I think, ultimately related to the famous "know thyself" of the Delphic oracle.

Then follows an extraordinary scene where Diomedes attacks and wounds the goddess Aphrodite, driving her off the battlefield. I can only explain this with help of the "wrath of Apollo" undercurrent of the Iliad: metaphorically it means that Aphrodite, sexual desire, has no place on the battlefield. The implicit meaning of the "Helen" story, the Chryseis-Briseis theme, Nestor's call to "not go home before we have slept with some Trojan wife" (Il 2.354-) is what the poet has in mind here, and what this metaphor attacks. Zeus confirms it (Il 5.428) and Homer shows it again in another scene: Il 5.352-, where Ares lends his chariot and horses to her. To have the horses and chariot means, metaphorically, to be in command: the Achaians are letting "lust" decide about war.

In Il 11.368- Paris shoots Diomedes in the foot with an arrow. The poet is probably connecting him again with Achilles though about the latter's death no details are given. Diomedes however does not get himself killed but instead withdraws behind the lines with some of the other wounded heroes. In the Iliad we will not see him on the battlefield anymore. Of course, to be wounded is a valid excuse for not joining the battle anymore. But... if I am not mistaken, in an intensely heroic warrior-society like Homer's world, I think it might be slightly eyebrow-raising to be found only "encouraging from behind" when your city/army is on the brink of being solidly defeated. Manliness is everything after all: you are supposed to say "'tis but a scratch" and continue fighting. Agamemnon's retiring after his wound becomes like "the pain of a woman in childbirth" (Il 11.269-) is no less than a harsh condemnation of him in heroic terms.

It is the clever, experienced ones who are to be found behind the lines: Agamemnon, Odysseus, Nestor, Idomeneus. The young and inexperienced ones (plus Aias) are to do the actual fighting. But we can not accuse them of cowardice, after all they are wounded.

This is not so different from Achilles, who is, or acts like he is, mentally wounded by Agamemnon's insult. It should be noted that both are favourites of the goddess Athena (though in book 11 she does not appear to Diomedes, nor does he pray to her). Her gift of success in war means to be a great hero and come home again. This is a gift Achilles ultimately cannot take.

There is another road to heroism in this world, one that Nestor is the paradigm of: the hero of the assembly. He is the one who wins all debates with his "sweet voice of heroism". This is a phenomenon of all times: once an enemy is identified, heroic talk ("let's teach them a lesson", "never give up", "when the going gets tough, the tough get going") is always more popular. It appeals to our masculinity and anyone talking differently is therefore less than a man. Diomedes quickly learns this, becoming Nestor's favourite (Il 9.29-, 9.696-).