The dramatic climax of the Iliad is the killing of the leader of the Trojan army, Hector, by the

Achaian hero Achilles. The latter is irresistible in his blind fury and revenge because Hector was

the killer of Achilles' friend Patrocles. All by himself, Achilles slaughters half an army. This

fury, mēnis, is the first word of the Iliad and its primary theme. Mēnis is a word that is used only

for gods and for Achilles. It is often appropriately translated as "wrath". This scene you might call

the epicenter of the Iliad.

Just before that moment Zeus, the god of Fate, balances his scales, symbol of Justice, in an iconic

gesture measuring the Kēres (doom) of the two heroes. Hector's side goes down to Hades,

Achilles' Kēr goes up (towards Ouranos, heaven). So it goes. For a long time I wondered if that was

Homeric Justice.

Achilles, although a Greek, is a furious monster. His friend Patrocles has only himself to blame

for his death, Homer makes that very clear. Hector, although a non-Greek, is a real mensch, a

hero we would like to be, giving his life for his wife, child and city. This, too, is shown with

great emphasis and pathos. This is a really curious contradiction in the rhetoric of the poem. Still, it is Zeus who

holds the

scales, i.e. makes the judgement. How is this just?

If the god of Fate is also the god of Justice, and Fate is "what happens", does that mean that everything that happens in the world (or in the Iliad) is just? We know better than that.

But, as always, the answer is provided within the picture. Balancing scales that go down on

one side, are of course not "straight", not just. Scales that are perfectly balanced are the

image of justice (Il 12.433-(1)). This Zeus with his unequal balance is showing us a judgement

that

claims justice but is really one-sided only. It is only just from Achilles' point

of view.

Homer does not tell us this, we are supposed to see this ourselves. It is this image that

made me understand that Homer's gods are not absolute. They are not beings "out there", distinct from us, but phenomena:

we see and evaluate the world through their eyes subjectively.

Achilles' mēnis is the wrath of Zeus, but it is the Zeus of Achilles. The latter is filled with

Justice, or rather self-justification. First in his anger with Agamemnon, later in his

implacable fury with Hector, for taking Patrocles (i.e. his honour) away from him. But is it Zeus who tells him to

act this way? Actually his behaviour

is driven by other gods.

Homer shows this, too (Il 1.212-, 18.356-)(2). Achilles does not know himself.

So far, this is clear. But it leads to an ethical paradox:

The image of the scales is about your share (Moira or Aisa = share = fate). The

archetype is the sharing out of booty by the commander after a successful raid, or the

share one gets in the common feast meal where everybody gets his portion according to

status (Il 4.257-). Seen as a one-to-one transaction, the question is: how much for me,

how much for you(2). The measure of my justice is the proportion I assign to myself.

This points to one of the motto's of Delphi: Mēden Agan, "not too much". The winner cannot take it

all. There must be a balance weighing two portions. Zeus is the god, the only god,

who knows the other person. All the other gods know only one: "me".

So the size of my portion is the measure of my injustice (in your eyes). If you get

nothing or less than you think you deserve, you are in your own eyes perfectly just (and angry).

The loser of the judgement goes to Hades, literally or figuratively. Homer has a little pun with a deeper meaning:

The people in Hades, having no share in anything, are by the law of the balance

the most just people.

The poet probably associated the word "Hades" with "not being seen" e.g. Il 5.845), just as

he associates the mountain "Idē" (seeing) with Zeus' favourite lookout(3).

Justice is dependent on seeing - seeing the rights of the other person.

Here lies the problem of judging: one of the parties is judged to be in the right, his side

of the scales will go up. The loser finds himself disregarded, unseen. But this

makes him automatically the most just (in his own eyes)! And if this Zeus comes down to

earth, you had better beware...

Here, as is shown by the figure of Achilles, is the paradox of subjective justice. Zeus is not only a loving god who tells us to share equally, he can also be a harsh and unreasonable god. Zeus is a god to be feared, the god of vengeance. There are echo's of the bible here. The problem lies in our judging: when we judge we hold the scales, we take a position that we should not, because we do not have the "god's eye view", we only know ourselves. Adam and Eve's sin is not so much the disobeying of a command, it is the judging, the presumed knowledge of good and evil.

Here also lies

the root of the problem we have with understanding it: Zeus does not mean absolute

justice, it means Achilles' - our - justice. The absolute (in Greece) was only invented or properly

formulated by Plato. This immediately raises questions about Zeus. Relative justice? That

does not mean anything at all. It only means that everybody thinks himself just.

But: before writing off Zeus as "relative", we should first make sure that the god

we are obeying is really Zeus. Do we know ourselves well enough to be sure? In the case of

Achilles there is a telling scene at Il 18.356-. Zeus says to Hera: "So, Queen Hera, you have gained

your end, and have roused fleet Achilles". Was it not part of the "plan of Zeus" that Achilles

would be raised? This bears thinking about. What is really the source of Achilles' mēnis and

of his rampage and hatred of Hector? Is it really Zeus or does he make himself believe that it is

Zeus?

To see why Zeus would still be a worthwhile god, we need to take a detour to Plato.

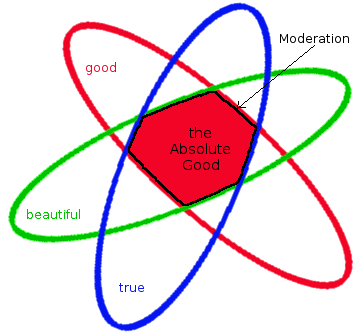

So, how can we live with this? We already ate from the tree and there is no going back. Does the freedom we have under Zeus make itself impossible? Plato would affirm this and proceeds, in the Republic, to abolish it. What we need according to him, is a sovereign Idea of the Good that is to be the philosopher-king's guiding light. This is quite different from the Rule of Zeus. Let us compare Zeus' order with that of Plato:

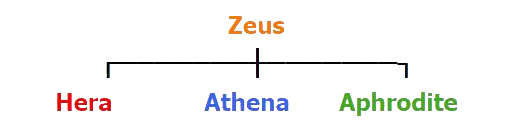

Homer's gods

Plato's Good

Zeus is supposed to be in charge. He boasts of being stronger than all the

other gods together but

appears to avoid putting it to the test. See "the golden rope", Il. 8.19. Hera

is number two though she

wants more, Athena is Tritogeneia, third-born (just as Zeus became first-born)

and

Aphrodite is fourth, though sometimes stronger than Zeus himself.

The solid red part is our Nomos, its border is Sophrosyne

The picture of Zeus, father of gods and men, is that of the pater familias who should be in charge of his family. He boasts that he is anyway (Il 8.5-) but, as befits a god of Justice ("Justice" meaning that you cannot have it all your way, see Th 535-) he often gives in to the desires of the other gods (see Il 4.20-). In human terms this means that we often give in to our selfish desires rather than obeying our "better selves". Zeus is the god of compromise, a god who is vulnerable to the "stronger than his father" trope.