The gods of Plato

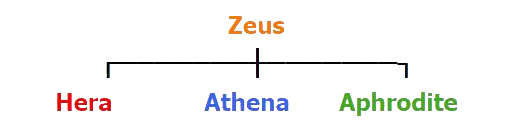

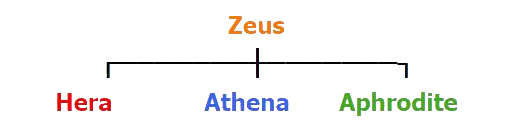

In the Republic, where Plato develops his soul - city analogy, Plato never mentions that

the three parts of the soul correspond to the three main goddesses that Homer talks about.

They have the same roots, though. Gods and Goddesses can not only convince individuals to obey them,

groups and whole communities can be under their influence. In the Laws he goes a bit deeper into the

theory of how he

sees the gods. He calls it (or them) soul (Psychē), the soul of the world.

Plato Laws X, 891C-: a summary

- "Fire, water, earth, air", things of the body, are not first

- "Soul" (psychē) is first, because it is older than body

- "Things of the soul": opinion, thought, art, law etc. come before concrete things.

- the works of "technē" come before the things of nature, which is wrongly called "physis"

- Soul itself, being first, should be called physis

- and it is the prime mover, which is life.

- so the soul is the cause of all things fair and foul, just and unjust and all the opposites. (896D)

- soul also controls heaven

- but not fewer than 2 souls: a beneficent one and an opposite (unreason)

- This is Plato's purification of the gods: he splits off the bad.

He creates evil & virtue by this separation.

- Here he makes "new gods" (896E). Nice of the anonymous Athenian to answer for Clinias!

- thus are caused all the "motions" like thought, joy, fear, confidence etc., but also the things like

hardness, wetness, the things of the body, all in conjunction with either reason or unreason.

- and, the world being what it is, it must be a reasonable and beneficent soul who is in control of

heaven and earth

- since "moving in place" (rotating) is eminently more "reasonable" than moving about all over,

the gods are not moved themselves, they only move us.

This is beyond Homer of course but the kinship should be clear. Plato does not mention gods but he talks

about what moves us mentally. These are things

"of the soul", the immaterial active principles, the ideas, that underlie everything. We are talking here about forces or we should rather say powers. In the previous page we saw the domains of these powers. Homer makes it clear that they can act on both individuals and groups such as communities or armies. It should also be clear that the Greek gods move

us as well as what we call the natural world (stars, planets, the weather etc.). Homer is interested mostly in their acting on humans. The Greeks distinguished a number of distinct "specialized" powers which tell us what to do if they so choose. They also anthropomorphised those powers. They are beyond our control - we can only pray to them, put our faith in them, but they remain unpredictable. But if they do speak to us, we had better obey. For the creation

of one out of three - in European thought(1) - we have to thank - or blame - one man in particular: Plato. He philosophically merged the three main goddesses into one and tried to cleanse them of the worldly muddiness and very human partiality that they show in Homer. Plato's gods cannot be swayed by prayer or gifts and they are

absolutely good; see above: the bad has been split off. Thus he paved the way for the

monotheism that was to come, though he himself does not completely go there.

Plato develops this into his theories of the three parts of the human soul, and the three classes of people: the desiring class, i.e. the common people or "money-earners", the aristocracy or guardians and the reasonable part, the ruler(s) or philosopher-kings.

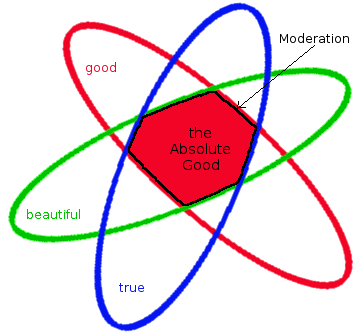

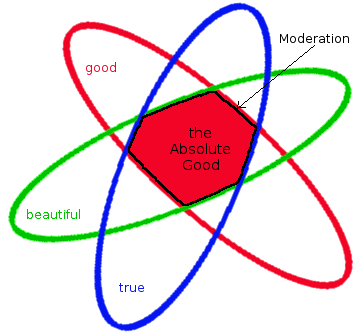

Below is a visualization of the theory. It is somewhat simplified compared to the examples in Plato's writings but I believe this is his point. See e.g. Rep. 433B and the Philebus dialogue.

Zeus is supposed to be in charge, but is he? He boasts of being stronger than all the other gods together but appears to avoid putting it to the test.

Hera his wife is number two with a bullet,

Athena is third though the most effective of the lot,

Aphrodite is fourth, though sometimes stronger than Zeus himself.

The solid red part is our Nomos, its border is Sophrosyne (moderation)

Homer's gods have been explained (hopefully) on the previous page. Plato's view he gives in

The Republic and other dialogues. A complete treatment of these would be too much (even supposing I

could do it): read

those works yourself. We will summarize them by starting at the end and working back to Plato's

starting question in the Republic: what is Justice?

Plato has an Idea

Plato purifies and objectifies the three main goddesses with a view to building his kallipolis.

Why did he not clean Zeus of his subjectivity?

This turns out to be easier said than done. How do human beings create an objective Justice?

A partial answer

is "the law" and he goes that way in his later work. But with or without law, we still have to do the judging

and - see above - we are not equipped for that. Perhaps if we become true philosophers, if

such creatures exist. Plato knows this very well, it must be why he creates one of his "noble lies": there will

be justice after death. This theory has the advantages that no one can check it and that people

who believe in it may behave better in this life. Philosophically I think it is a chutzpah: "we cannot

have it here but believe me, the miscreants will pay for it after death (..so don't interfere!)."

Note that there is some level-confusion about Sophrosyne (moderation)(1). In the text of Rep. 433B he uses the word as a limit only of the sensual desires, Aphrodite or the desiring part of the city. In other places (e.g. Charm 161B) he defines it the way Justice is defined here: doing one's own thing. In the picture above, moderation is the limit of the intersection of the three domains. This means, in Plato's view: Moderation is Justice. So what we have here is a

bound Kronos: all gods in one but bound by moderation. Zeus has disappeared.

Here he says that if we have found our "σωφροσύνης καὶ ἀνδρείας καὶ φρονήσεως", i.e. moderation, courage and prudence (the tamed versions of B, G and T) then what we have left is Justice. In other words: if an act is all three of these, then it must also be just.